I’m kicking off my report in Dar Es Salaam, the city that, as I’ve learned, is no longer the capital of Tanzania—that title now belongs to the lesser-known Dodoma inland. However, Dar is undeniably the most important city in Tanzania due to its large port, which serves as a hub for global trade, especially with China. All volunteers heading to Liuli start their journey from here.

Before we depart Dar for Liuli, I’d like to share a bit more about the city. With over five million inhabitants, Dar Es Salaam is considered the economic and cultural heart of Tanzania, boasting 575 major industrial companies and several universities, according to Wikipedia. Despite this, after spending a few days in Dar, I get the impression that many people here still lack stable jobs or education and must earn a living daily by selling items on the streets. For example, you’ll find vendors selling bags, flip-flops, and watches, as well as nuts, fruits, and drinks to passersby. We’re constantly approached as we walk by, with people expecting us to have money to spend. I rarely find anything among the goods that genuinely interests me. We’re also persistently offered taxi rides. On the “beach promenade”—a noisy, bustling street right next to the Ferry Terminal that doesn’t quite deserve the name—we’re approached very aggressively, with vendors trying to sell us ferry tickets to Zanzibar. It’s clear that the locals are staring at us because our skin color makes us stand out as wasungu (white Europeans). It takes a bit to get used to this, as I notice a certain scepticism in their often serious expressions. We also visit a Protestant church built by the Germans during the colonial era, which is still supported by a German congregation. The organ is brand new, as mentioned by a man who appears to hold some official position in the parish. We only intended to take a quick look around the church, but he engaged us in conversation and offered to show us around. We didn’t resist and followed him up to the bell tower, where we enjoyed a magnificent view over the bustling city center. When we returned, he asked us for a donation to the church, which we gladly placed in an envelope he held out to us. As we were about to leave, he stopped us and asked, “And what about me? Coca Cola?” I felt a bit disappointed, but we gave him 2,000 shillings. He seemed disappointed too, even though 2,000 shillings is enough to buy a Coke as a Local Our farewell was no longer as warm. During our stay in Dar Es Salaam, I realize how challenging life must be for those who rely on daily deals without a stable income. I also notice how crowded the streets are during the day, with people sitting or standing everywhere, seemingly without any obvious purpose. Some greet us with: "MsunguLater, a local taxi driver explains that this is part of Tanzanian culture and that many people prefer this way of life. In the end, we’re left to ponder and let these impressions sink in. Tim, who has been to Tanzania before, tells me that the rural regions of the country are vastly different from the urban areas.

From Dar es Salaam to Ilembula

We began our departure from Dar Es Salaam with our first stop en route to Liuli: Ilembula. There, we visited the Kronenberg couple—he is a surgeon, and she is a pastor. Both have been connected to Tanzania since the 1990s, living and working in the country with their family from 1996 to 2000. Since 2019, they have returned to Ilembula, this time without their three grown-up children.

Our journey started early in the morning as we made our way to the Mbezi bus station in Dar Es Salaam. Reporting timewas set for 04:00, with the bus scheduled to leave at 04:30. To ensure we were on time, we had booked a cab to pick us up at 03:00 the day before. Despite the early hour, the bus station was far from deserted. It turns out that 04:00 is a popular departure time in Tanzania. I'll discover why later. We requested the cab driver to take us directly to the bus because navigating the city center without fluent English proved challenging. With buses parked in at least 50 different bays and no signs indicating destinations, we had to rely on the assistance of Watanzania In fact, the driver leads us to the one parking bay where there is no bus parked. We say thank you and wait. A long wait, because the bus does not arrive at the announced Reporting timeMeanwhile, other buses continued departing for Mbeya from different companies. We had to repeatedly ask in Swahili whether this was our bus. Every couple of minutes, a vendor approached us, offering various goods like headphones, shoes, bags, or snacks. I searched in vain for a decent breakfast amidst the offerings. Finally, when the correct bus arrived, we quickly stowed our luggage and took our seats. The bus was packed, loud African music blared from the radio, and somewhere in the boarding area, a constant beeping echoed. To block out the noise, we donned our sleep masks and earplugs and managed to nod off. Upon waking, we realized we had long left the city behind. To our right, unfamiliar trees and bushes blurred past as villages filled with people and motorcycles sprang up. Life here takes place on the streets. The bus maneuvered through impossible overtakes to pass the many trucks transporting petrol to remote regions of Tanzania and neighboring countries. This road is the sole connection between the interior and the port of Dar Es Salaam, making it exceptionally busy. Tanzanian coaches lack toilets, adding to the challenge of a 12-hour journey. After about 4.5 hours, we made our first stop. Unsure of the exact duration, we hurried to the chooni ) to grab a quick breakfast before rushing back to the bus to avoid missing our departure. Tim has had to do this before, boarding rolling buses in a similar fashion. As we continued, we passed Mikumi National Park, experiencing firsthand why Safari means "journey" in Swahili. We glimpsed giraffes, zebras, wildebeests, antelopes, and monkeys—an awe-inspiring sight. Beyond Mikumi, the landscape grew more mountainous and the road increasingly winding, with daring overtaking maneuvers becoming more frequent. Despite the challenges, we arrived in Iringa for another brief stop before finally reaching Halali village after a 12-hour journey. It dawned on me why buses depart Dar Es Salaam so early in the morning. In Halali, we were greeted by Werner Kronenberg, who then took us to Ilembula.

Ilembula Lutheran Hospital

Upon our arrival at Ilembula, we were warmly welcomed by the Kronenberg family. We eagerly anticipated spending an entire day with Werner, who serves as a surgeon, and receiving a comprehensive tour of all the hospital's departments. Our day began with a shared Chai ya asubuhi , followed by the morning service in the hospital chapel. We then attended the early doctor's meeting and concluded with rounds of surgical patients in various wards, including the Intensive Care Unit, Pediatric Surgical Ward, Men's Surgical Ward, and Women's Surgical Ward. Ilembula Hospitali is significantly larger and better equipped than St. Anne's Hospital in Liuli, our final destination after a long journey. The hospital boasts a fully functional laboratory capable of performing blood counts, microbiological, and parasitological analyses. Additionally, there is a blood bank stocked with blood preserves for transfusions, a well-supplied pharmacy offering a wide range of products, and a state-of-the-art digital X-ray machine that produces exceptionally clear images. Together with Werner, we reviewed numerous fracture cases on the X-ray, highlighting the prevalence of road accidents, particularly motorcycle accidents, which are a daily occurrence here. Surprisingly, surgery is only occasionally necessary, as many injuries can be effectively managed with conservative treatments like plaster casts. This experience solidified my resolve never to ride a Tanzanian motorcycle taxi. As we toured the facility, we noticed that some of the buildings are very modern, such as the new operating wing equipped with two advanced operating theaters. This visit underscored how much we still have to learn about securing funding in Germany. Tim, who has been acquainted with the hospital in Liuli since 2019, was continuously inquisitive about the care options and resources available at Ilembula HospitaliOur goal is to absorb as much knowledge as possible to bring back to Liuli and enhance medical care there. We encountered many friendly Tanzanians at the hospital, who welcomed us with a heartfelt Karibuni sana Fortunately, communication was smooth among the hospital staff as they converse in English with each other, although most patients primarily speak Swahili.

Throughout the day, Werner involved us in several medical procedures, allowing us to step into the role of doctors. We examined an old man with acute abdominal pain and decide that he should be observed first, as we think a blockage is more likely than an intestinal obstruction, although the X-ray looks a bit more dramatic. It turned out that the decision was exactly right, as the man was able to evacuate, and the pain subsided. We then applied a plaster cast to a lower leg fracture. At one point, we encountered an 18-year-old female patient with persistent swelling in her right forearm and hand for three weeks following a fall. Despite a negative X-ray for fractures, the patient experienced excruciating pain upon slightest touch. An infection seemed unlikely as the skin was intact (no entry point for bacteria) and the arm was not overheated. Something rheumatologic perhaps? Or the rare complex regional pain syndrome?Patients like this often fall through the cracks. Unable to conclusively diagnose, we prescribed strong painkillers and prednisolone, and Werner advised a follow-up visit in two weeks. Later in the day, Tim had the opportunity to assist with a proctological surgery, while Werner guided me in performing an abscess incision on a breast. By the end of the day, we were exhausted yet immensely satisfied, enriched with numerous new insights that only heightened our anticipation for our upcoming experience in Liuli.

From Ilembula to Songea

Our journey to Liuli continued as we prepared to travel from Ilembula to Songea. Although the hospital's physiotherapist had reserved seats for us on the 08:30 bus in advance, several buses from the Super Feo Express travel company passed us by first—they were too full. We had to call the hospital again to secure another reservation and were finally able to board a bus at 11:40. Due to the lack of available seats, I ended up sitting on a seat mat in the entrance area, hoping the bus wouldn’t have to brake hard. After about 40 minutes, the bus made its first stop, and I managed to grab a vacant seat. For the next four hours, we travelled through untouched, mountainous landscapes, only occasionally interrupted by small villages with corrugated iron-roofed houses. The cell phone network here is very limited. Since hardly anyone on the bus seemed to speak English, we were confused about which bus stop to get off at on our way to Songea. Eventually, we got off randomly at the second stop and found ourselves on a dusty street lined with stores and, most notably, numerous motorcycles. The owners immediately wanted to load us up with our luggage and transport us. We insisted on being taken in a bajaji (tuk-tuk), and one was promptly brought for us.

We stayed in Songea for three nights, booking into a hotel that the hospital secretary from Liuli had described to us as nice and cheap . Cheap It was indeed cheap—15,000 shillings per night (approximately €5.50)—but unfortunately, there was no running water in the bathroom, and the toilet was traditional Tanzanian style, meaning we had to make do with a hole in the floor connected to a sewage pipe. However, we were immediately provided with a large green bucket of warm water, which, judging by the smell, had just been heated over a fire, and a small bucket for rinsing, showering, and washing our hands. Given the fist-sized holes in the mosquito net (at least there was one), we were grateful for our malaria prophylaxis.

Songea

Wir treffen uns mit Dr. Ndimbo zum chai ya asubuhi We met Dr. Ndimbo for chai ya asubuhi at our new regular restaurant, where we now have all our meals. He greeted us warmly with a hug, and we got to know each other a little. Dr. Ndimbo hails from Liuli and not only began his medical career there but also practiced as a general doctor at St. Anne's Hospital for many years. He knows a great deal about Liuli, the origins and development of the hospital, and is happy to share his experiences with us. We asked one question after another to gain a better understanding. “How have tropical diseases evolved in the region?” we inquired. The doctor informed us that they now very rarely encounter cholera, dengue fever, leprosy, onchocerciasis, or schistosomiasis. Classic childhood diseases, including measles, tetanus, diphtheria, and many other vaccine-preventable illnesses, are also seldom seen here, as newborns are vaccinated promptly after birth. I also learned that the population receives a single dose of anti-parasite medication every year. In contrast, malaria remains the most common reason for treatment at St. Anne's Hospital, but I’ll share more about that when we arrive in Liuli.

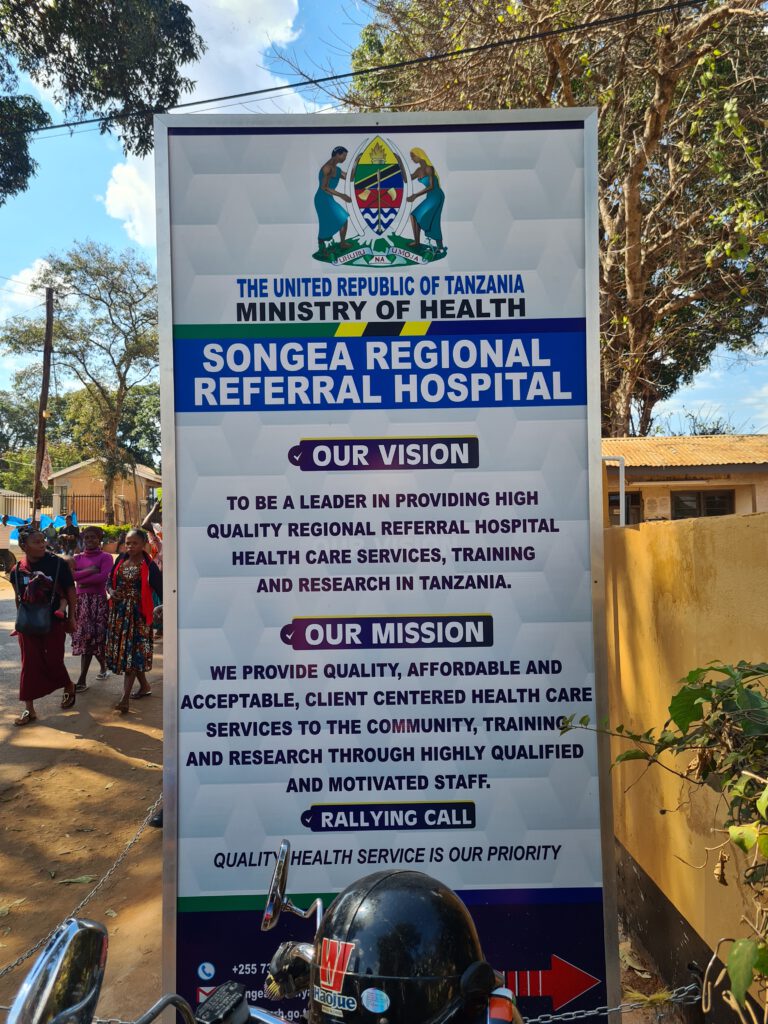

After breakfast, Dr. Ndimbo took us on a tour of the Songea Regional Referral HospitalI was truly impressed by the hospital's resources. They have an excellent laboratory capable of conducting even specialized hormone tests, a recently purchased computed tomography (CT) scanner, and a dental practice equipped with a dental X-ray machine. It's evident that the government is heavily investing in this state-run facility, and I felt delighted for the residents of Songea. In contrast, we can only dream of such facilities at the Anglican church hospital in Liuli, where we don’t even have a stable power supply and the roofs are leaking. I thought to myself that medical care is really very unevenly distributed.

After shaking many hands and asking countless questions, Dr. Ndimbo showed us his workplace—the School of clinical officers, a professional group that falls somewhere between nursing and medical staff. There, we spoke with Dr. Ndimbo and the deputy principal about one of Liuli's biggest challenges: the lack of staff. The village is so remote that most doctors do not stay longer than two years. Moreover, the two doctors currently working are not employed by the government, which means the hospital has to cover their salaries—a difficult task, as we know. Although Liuli is remote, it has direct beach access to the beautiful Lake Nyasa, we were told, but Dr. Ndimbo and the principal only smiled slightly. They also discussed the high unemployment rate among doctors in Tanzania. We couldn't understand why unemployed doctors wouldn't want to work in Liuli for slightly less money instead of not practicing medicine at all. They couldn’t or didn’t really want to explain this to us but talked about financial incentivesincentives to lure doctors from Songea to Liuli for a few days or weeks. We let this information sink in and focused more on the School of clinical officersThe training lasts three years and, similar to Germany, includes both theoretical and practical units. The students receive a relatively comprehensive overview of many different medical specialties, it seems. It just doesn't delve into as much detail as in medical school, we were told. The biggest challenge at the school right now is the lack of computers, which are urgently needed for teaching. Dr. Ndimbo and the principal therefore asked us to use our contacts in Germany to find donors for two laptops. We ended up meeting the graduating class, who have to sit their exams in a few weeks. We received a very warm and enthusiastic welcome and were asked to take a group photo, a request we were happy to comply with.

We also used our stopover in Songea to meet Dr. Hinju for dinner at our local restaurant. He is an ophthalmologist and also feels very connected to Liuli. We actually wanted to invite him to visit St. Anne's Hospital regularly and treat patients, as there are no eye specialists in the Liuli area. But Dr. Hinju told us that such a visit was already being planned, and we were very happy about this news. Eye diseases are very common in and around Liuli. Many people suffer from impaired vision, but there is usually no access to visual aids. Dr. Hinju and his team are therefore a great asset to St. Anne's Hospital.

On our last day in Songea, we met Mr. Gift, the hospital secretary, who ran some errands with us in Songea. We bought a few items of equipment for the Doctors House, where we will be living for the next two months. We then went to a pharmacy together to place a bulk order for medicines and hospital supplies. Tim found out exactly which medicines are sold in the pharmacy, and we also bought some preparations that were not on Mr. Gift's list, such as intravenous oxytocin to treat heavy bleeding after a birth. When we checked the order at the end, some items were missing and still had to be provided by the pharmacy staff. However, there were also items that we didn’t pay for at all or at least not in the quantity we paid for, so it all balanced out quite well. In the end, we spent Tanzanian shillings in the millions. We loaded up the jeep that Mr. Gift had brought to Songea, and our luggage had to be strapped to the roof to make room for the medication and for us in the back. We ran errands in Songea, as there is no large pharmacy in Liuli, only the tiny Duka La Dawa (medicine store), which is more like a mini drugstore. There are also no ATMs in Liuli, so we stock up at the machines until we reach our daily limit.

After the shopping trip, we drove to the Anglican diocese to meet the Bishop of Ruvuma in person. As it turned out, the bishop is an incredibly friendly, polite, and thoughtful man. He profusely thanked Friends of St. Anne's for all their support over the years. He also acknowledged that Tim is an exceptional, highly motivated, and committed first board member of the association, and I have to agree with the Bishop. We arranged to meet him again in September to discuss new projects at the hospital.

In the afternoon, we got into the packed jeep and headed south. We finally had our final destination, Liuli, in sight. Soon after Songea, the surroundings became more mountainous and the road more winding, but also less busy. We climbed higher and higher under a sun that was already in the west, and I realized that the area is truly beautiful. For the first time since my arrival in Tanzania, I felt that nature still rules over people here, not the other way around. Only now did I realize that some things about the cities really bothered me, namely the garbage, the crowded streets, and the constant alertness needed to avoid being hit by a passing motorcycle or car. We passed small, sleepy villages, with farmland stretching across the hilly landscape in between. The setting sun cast a beautiful light on the hillsides, which glowed in shades of brown, red, yellow, and green. After Mbamba Bay, the asphalt road turned into a dusty dirt track. This didn’t seem to bother the driver, as he continued at the same speed. I was told that it was only a few kilometers to Liuli. The sun was just setting over Lake Nyasa, and I was really looking forward to seeing so many beautiful sunsets over the next two months. Shortly before we arrived, I experienced a brief Bali vibe, even though I’ve never been to Bali before, as rice fields stretched as far as the eye could see to the right and left of the road. We finally arrived in Liuli. The sun had already set completely. We were already expected at the Doctors House and were helped to unload our luggage and medicine boxes. There were still two medical students from Vienna at the Doctors House, with whom we chatted a little and had a delicious Tanzanian dinner before falling tired into