As we arrive on a Saturday evening, we spend the following Sunday resting from the long journey. Monika, the cook and housekeeper at Doctors House, prepares breakfast for us of fried rice balls, which we eat with the hazelnut cream we bought in Songea. Afterwards, Tim, Ulrike, and the fourth member of the group, also named Sara, take me on a walk to explore the village of Liuli. We start at the beach, just a minute's walk from the Doctors House along a tropical wooded path. I’m the only one wearing open-toed shoes, and Sara jokingly offers to go ahead of me and chase away any snakes. While it doesn’t seem like snake bites are common here, I appreciate her thoughtfulness. Lake Nyasa also known as Lake Malawi, has a slight swell due to its vast size. The shoreline in our section is picturesque, featuring small rounded rocks, water grass, and the Sphinx—a stone formation rising out of the water about 50 meters from the shore, which does resemble a sphinx in profile. Tim reminds me that Liuli was once called Sphinx Harbour during the German colonial period. All that remains of the harbor are the rotting wooden pillars of the former jetty, though we’re told a boat still docks here weekly to transport passengers northward along the lake.

The beach also hosts Joseph’s Paradise, a beautiful complex of bungalows and a beach bar, surrounded by palm trees and colorful leafy shrubs. It’s clear that the landscaping has been done with great care. Tim, who knows Joseph from his last trip to Tanzania, asks him when he last hosted guests. February, Joseph replies, suggesting that the lack of online booking options and Liuli's remote location might be factors. Tim immediately offers to help Joseph set up a website.

From the beach, we stroll towards the town center. It doesn’t take long before we encounter the first cassava fields. Cassava is a root crop that Tanzanians use to make Ugali , a staple starchy porridge. Most of Liuli’s inhabitants are farmers, while others make a living by fishing in the lake. However, Ulrike and Sara mention they’ve heard that fishing is poor at the moment, leaving people with less money to visit the hospital. We eventually reach the main road and greet residents with the typical Tanzanian greeting „Habari za asubuhi?“ (News of the morning? Or, in other words, how are things this morning?) The common replies are „Salama/ nzuri/ safi“ meaning peaceful, splendid, or good. To younger people, we say „Mambo“ (Everything cool?) and they respond with „Poa“ (cool) or „Fresh!“. Greetings hold great cultural significance in Swahili. Older or more respected individuals are greeted with „Shikamoo“ to which the reply is „Marhaba“ (You have my blessing). Walking along the dusty main road (like all roads in Liuli), we draw attention as Habari-Grußformel, sodass es beim Spazierengehen eine Menge salama, nzuri und safi (You have my blessing). Walking along the dusty main road (like all roads in Liuli), we draw attention as Wasungu . Many children approach us with radiant smiles and enthusiastic waves, shouting „Wasunguuuu!“. Older children are more shy but wave back after we greet them. The youth here are used to seeing white visitors, as European volunteers are often present in Liuli.

The Hospital

St. Anne’s Hospital in Liuli is a small facility with around 100 beds but serves as a critical healthcare provider for the residents of the Ruvuma region due to the area's poor infrastructure. Currently, two doctors work alongside a team of Clinical Officers und Nurses . The hospital is modestly equipped, with an analog X-ray machine, an ultrasound machine, a 3-channel ECG (compared to the 12-channel ECG standard in Germany), and a laboratory capable of performing blood counts, urinalysis, stool microscopy (for parasites), and rapid tests for malaria, typhoid, and Helicobacter pylori. There are two basic operating theaters, an Outpatient Department (OPD)akin to a family doctor's office or emergency room, and an HIV outpatient clinic. Common conditions treated include malaria, typhoid, accidental injuries, and obstetrics, which includes both spontaneous deliveries and caesarean sections. While treatment for malaria and HIV is funded by the government, most other services require out-of-pocket payment unless the patient is insured—a rarity in this region, limited mostly to government employees like teachers, doctors, and civil servants.

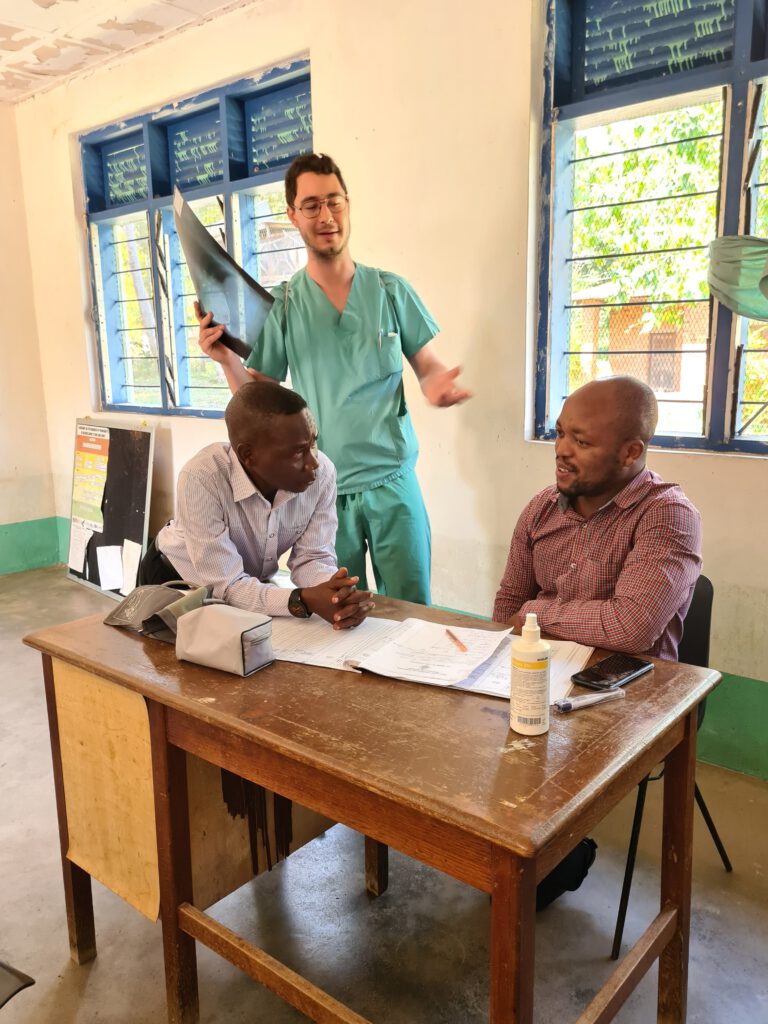

On Monday morning, Tim and I introduce ourselves at the early meeting. We are warmly welcomed by the hospital staff. We also immediately hand over our gifts, which include a neonatal resuscitation manikin, respiratory masks and bags and a total of 19 kg of specialist literature on all the important medical specialties in Liuli. We then accompany Dr. Evans on a tour of the obstetrics department and the women's, men's and children's wards. Dr. Evans translates what the patients say to him into English and also into Swahili if we want to ask questions. We really enjoy discussing diagnostics and therapies together and finding out how things work at St. Anne's Hospital. On the "prenatal" ward, we meet a patient who is already a few days past her due date and, we are told, is complaining of back pain. By taking an in-depth medical history, we find out together that the patient feels a burning sensation when urinating. Together we prescribe a urinalysis, which confirms our suspected diagnosis of a urinary tract infection, a possible reason for the prolonged pregnancy. The patient is given an antibiotic. A hospital employee has just been admitted to the women's ward with severe upper abdominal and chest pain. I suggest that an ECG be performed. At first they say there isn't one, but when we ask the radiology assistant, he gives us a 3-lead ECG - not ideal for detecting a heart attack, but better than nothing. The ECG is normal. We continue to consider a gastric ulcer, as the patient has been taking Diclofenac regularly for years due to spinal pain. Dr. Evans first prescribes paracetamol and tramadol to reduce the pain and a stomach protection medication to treat the suspected ulcer. We also do an ultrasound of the abdomen and an X-ray to rule out an intestinal perforation, both examinations are unremarkable. During our hourly check-ups, the woman is already feeling much better. There are two young men in the men's ward who are being treated for typhoid fever. They are both on the road to recovery. In the children's ward, a two-year-old with a high fever is causing us concern. She has malaria and her mother tells us that the little girl has had three seizures at home. We measure the temperature again - 39°C - and then ask the mother to uncover the child, who is wrapped in four Tanzanian kitenge. We also have the hemoglobin value determined (Hb for short, the red blood pigment), which is 7.4 g/dl. So the little girl has anemia caused by the malaria. Dr. Evans explains to us, however, that there is no indication for a blood transfusion at the moment. We decide to check the Hb again tomorrow and otherwise continue with the current malaria therapy. The next day we see the child running around the ward and the mother

Daily Life

If it’s possible to speak of a daily routine after just a week in Liuli, we’ve already established some habits. In the mornings, after Chai ya asubuhi we join Dr. Evans for rounds, which typically last until around 11 a.m. Afterwards, we see patients together in the Outpatient Department (OPD). While we frequently agree on diagnostics and treatment, I sometimes notice significant differences in approach—for example, in the use of antibiotics. In Germany, we’re taught to use antibiotics sparingly, but here they’re considered an essential part of effective treatment. Broad-spectrum antibiotics like Ceftriaxon which are reserved in Germany for serious infections to prevent resistance, are used much more routinely here. We discuss cases and exchange knowledge, but I remain conscious that we are guests here. This mutual exchange is one of the most important aspects of our collaboration. I’ve also been learning practical skills, like how to examine a pregnant woman’s abdomen to determine the baby’s exact position. Obstetrics is such a central focus here that we’ve been able to assist with both spontaneous deliveries and caesarean sections. For me, this is especially valuable, as my only prior exposure to obstetrics was through lectures and seminars in gynecology. Interestingly, caesarean sections in Tanzania are performed by General Practitioner , whereas in Germany, they’re the domain of gynecologists.

After lunch, we usually shift to other activities. For instance, we’ve invited the Dental Technician Joyce (Joyful) for tea to prepare for the arrival of Dental Volunteers from Germany. Or we brainstorm potential hospital improvement projects and assess whether they’re feasible to implement. We also research foundations to which we might apply for funding. In the afternoons, writing has become one of my favorite activities. As sunset approaches, we often go swimming in the lake for about half an hour—a wonderful way to unwind. After dinner, we each spend time on our own pursuits until bedtime.